Gastroparesis is a disease or disorder of the muscles of the stomach or the nerves controlling these muscles that causes them to stop working. This results in the stomach taking too long to empty its contents into the intestine and an inadequate grinding of food.

More common in women. A hormonal link has also been suggested, as gastroparesis symptoms tend to worsen the week before menstruation, when PROGESTERONE levels are highest. Dysmotility can also affect men and children;

A study of 146 patients with gastroparesis. Seen over the course of 6 years, patients at a referral center demonstrated that:

• 35% had idiopathic gastroparesis. i.e. it "came out of the blue", and they didn't know why!

• 30% had diabetic gastroparesis;

• 13% had gastroparesis related to surgical injury of the vagus nerve;

• 7.5% of cases were related to Parkinson's disease or other neurologic conditions;

• 4.5% were related to intestinal pseudo-obstruction;

• Remaining 10% of cases included other miscellaneous conditions. Specifically connective tissue diseases, such as scleroderma.

Soykan I, Sivri B, Sarosiek I, et al. Demography, clinical characteristics, psychological abuse profiles, treatment, and long-term follow-up of patients with gastro paresis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2398-2404.

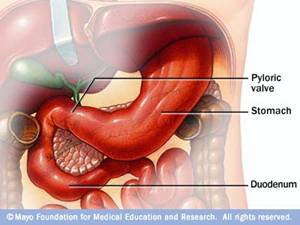

Normal Food path from stomach to small intestine. The stomach is a muscular sac about the size of a small melon, that expands when you eat or drink to hold as much as a gallon of food or liquid. The stomach mechanically churns and pulverizes your food while hydrochloric acid (HCl) and enzymes requiring an acid environment break it down. Muscle fibers of the stomach wall create structural elasticity and contractibility, both of which are needed for digestion and propelling food towards the intestines.

Pyloric Sphincter/Valve controls release of food from the stomach

- The pyloric sphincter(valve between stomach and intestines) stays closed while food is being digested in the stomach (to keep the food inside the stomach). During digestion, strong muscular contractions (peristaltic waves) push the food toward the pyloric valve, which is the gateway to the upper portion of your small intestine (duodenum);

- When HCl and the stomach enzymes have had enough time to do their job, alkaline bile (from gall bladder) and pancreatic juices (a watery bicarbonate solution) are secreted into the upper small intestine (duodenum). This prevents damage to the duodenum when the stomach's highly acidic contents are released;

- Once the duodenum has become strongly alkaline, the pyloric sphincter receives a signal to open, and the partially digested food is released into the small intestines. This is where most of the absorption of nutrients takes place.

• Chronic dehydration will prevent pyloric valve from opening. Due to dehydration, there is an insufficient water supply in the body's circulation from which the pancreas can produce the watery bicarbonate solution required to protect intestinal lining from stomach's acidic contents